Last week Lord Ganesh’s devotees observed the Sankashti Chaturthi. The word ‘Sankashti’ implies freedom from difficulties and pain, and Chaturthi is the fourth day of a lunar month as per the Hindu calendar. My mother prepared her usual offering to the Lord — Modak — fried dumplings with coconut and jaggery filling. On our routine call, she mentioned, “coconut prices have increased so much over the years while the size has become smaller. But, sugar prices haven’t changed much. In so many sweets, people now use sugar instead of jaggery, but that’s not good for our health.”

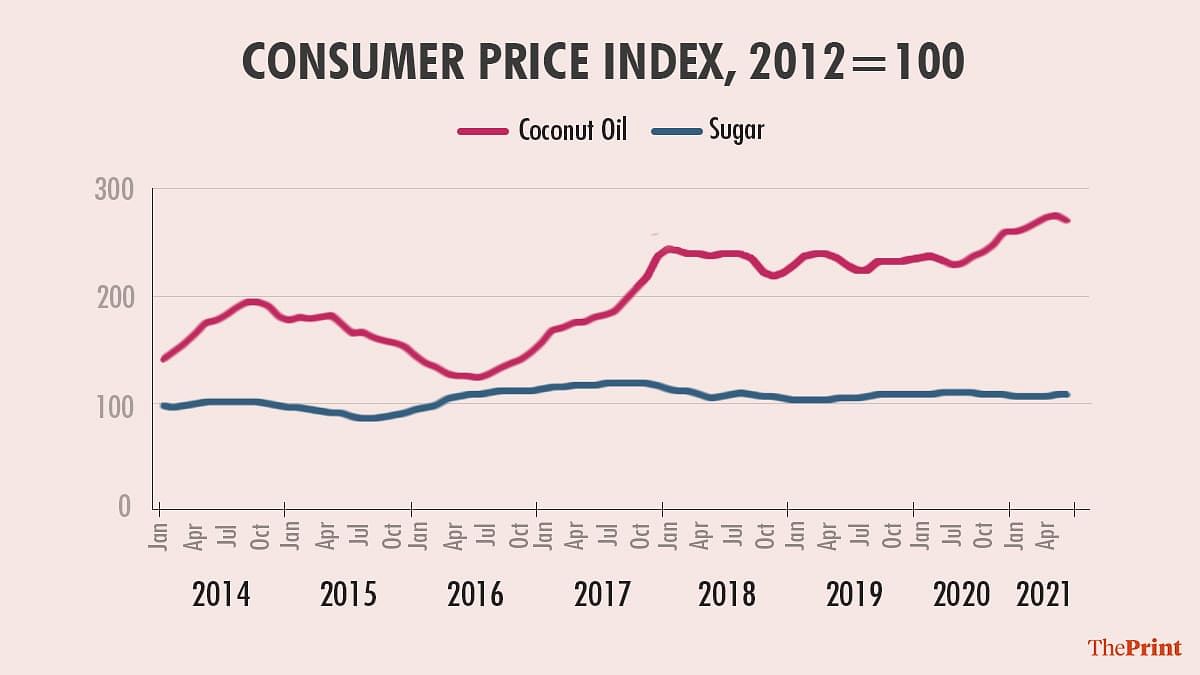

Indeed, according to India’s consumer price index, which captures changes in retail prices, coconut and coconut oil are among the products which have seen a rapid increase in their prices over time. To buy the same quantity of coconut oil that we bought for Rs 100 in 2012, we now pay around Rs 275-280. This is a higher price rise compared even to prices of products such as cigarettes that are taxed heavily. In contrast, for the quantity of sugar that we would have purchased for Rs 100 in 2012, we now pay only about Rs 10-15 more.

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrint

Graphic by Ramandeep Kaur | ThePrintA sustained rise in a price of a product takes place when, over time, the supply does not consistently keep pace with the demand. Temporary fluctuations may of course arise due to transient factors; for example, due to the halting of production during the Covid pandemic, or a seasonal jump in demand and a temporary drop in production such as in the cases of vegetables.

Sugar is one of the food products which has seen very little price rise in the last decade. Given the rise in prices of other food items during the same period, the relative price of sugar has dropped sharply. Given the increase in household incomes, the affordability of sugar has increased even more. It is consumed by a vast majority of households – almost 85 per cent – according to a 2011-12 report on Household Consumption of Various Goods and Service based on the 68th round of the NSSO survey. Despite its widespread use directly and indirectly in sweets and confectionery products, the supply of sugar has outpaced its demand with production concentrated in states such as Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka, keeping the prices under control.

Sugar production in India

India is the largest producer of sugar in the world along with Brazil. The OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030 report forecasts India’s sugar production to reach 35.6 million tonnes by 2030, accounting for over one-fifth of the world production. The report also expects India to experience the largest increase in consumption growth, fuelled by higher demand for sugar-rich confectionery products and soft drinks.

Given that we are one of the world leaders in sugar production, it may be tempting to believe that we have a comparative advantage in producing the raw material for sugar – sugarcane – that would make us competitive in the export market. But, we are unable to export sugar without the export subsidy due to high production costs compared to the other world producers. Despite the recent slashing of subsidies on sugar exports by the government, it still stands at Rs 4,000 per tonne.

Why do we, then, produce so much sugar that keeps prices low, encouraging more consumption not only of raw sugar but also processed confectionery products? Revising the previous system, the government announced a Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for sugarcane farmers in 2009. A NITI Aayog report released last year put the returns from sugarcane cultivation at 60%–70% higher than most other crops, and commented that “remunerative and assured prices along with improvement in yield and recovery continue to attract farmers to growing sugarcane despite ample supply… It would not be an exaggeration to say that India has structurally become a sugar-surplus nation.”

With farmers producing excess sugarcane resulting in higher sugar production, the market price of sugar tends to come under downward pressure. Sugar mills that procure sugarcane directly from farmers tend to find it difficult to pay their dues to them. As a result, in 2018 the government also announced the Minimum Selling Price (MSP) for sugar, which acts as a price floor. The NITI Aayog report recommended that the area under sugarcane cultivation be reduced by at least 3,00,000 hectares and sugar prices be revised upwards with a one-time hike. In addition, the government has also encouraged the production and blending of ethanol, which is made from sugarcane and molasses, into petrol to control pollution levels and reduce India’s oil import bill. India’s National Biofuel Policy 2018 aims for a target of 20% blending of ethanol in petrol by 2025 and 5% blending of biodiesel in diesel by 2030.

The Indian diet

Apart from sugary and processed foods, Indians have a diet heavily tilted towards carbohydrates, mainly rice and wheat. The Eat-Lancet reference diet recommends that 32% of calorie intake should comprise whole grains while in India it is 47% in urban areas and 58% in rural areas. The consumption is especially higher among poorer households. A glance at the CPI shows that rice and wheat distributed via the public distribution systems are now around 20% cheaper than in 2012. Recognising the poor dietary patterns, the government had launched a national nutrition strategy in 2017 to reduce all forms of malnutrition by 2030, with a focus on the most vulnerable and critical age groups.

Rice and sugarcane both are water-intensive crops with surplus production while India stairs at a severe water shortage. In states such as Maharashtra, in the drought-prone region, a significant share of irrigation is used only for sugarcane production. In effect, when we export sugar, we are exporting water with a subsidy.

The price of a product is not the sole factor, of course, when we consider how much we consume. For example, even among India’s richest 5% of the population, the calories from the protein sources have been estimated at less than half of the ideal reference diet. Nonetheless, for poorer households, the price factor continues to dominate, given relatively low incomes and low prices, and encourage excess consumption.

Coming back to my mother’s complaint about the price difference between traditional jaggery and sugar, we should put in place a strategy incentivising advanced technology in jaggery manufacturing and set quality standards. The use of jaggery as a sweetener instead of sugar would be healthier too.

The above news was originally posted on theprint.in. Credits- Vidya Mahambare is Professor of Economics, Great Lakes Institute of Management. She tweets @mahambare_vidya. Views are personal. (Edited by Srinjoy Dey)