India’s ethanol production programme has come a long way in the past five years, both in terms of the quantities supplied by sugar mills/distilleries to oil marketing companies (OMCs) and the raw material used — from cane molasses and juice to rice, damaged grains, maize and, down the line, millets.

Ethanol is basically 99.9% pure alcohol that can be blended with petrol. It is different from the 94% rectified spirit having applications in paints, pharmaceuticals, personal care products and other industries, and 96% extra neutral alcohol that goes to make potable liquor.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, at a G20 Energy Ministers’ meet on Saturday (July 22), said that India has rolled out 20% ethanol-blended petrol this year and aims to “cover the entire country by 2025”.

CANE OPTIONS

Till 2017-18 (December-November supply year), sugar mills produced ethanol only from ‘C-heavy’ molasses. The cane they crush typically has 13.5-14% TFS or total fermentable sugars content. Around 11.5% of it is recovered from the juice as sugar, with the uncrystallised, non-recoverable 2-2.5% TFS going into so-called C-heavy molasses. Every one tonne of C-heavy molasses, containing 40-45% sugar, gives 220-225 litres of ethanol.

But mills, instead of extracting the maximum recoverable 11.5%, can produce 9.5-10% sugar and divert the extra 1.5-2% TFS to an earlier ‘B-heavy’ stage molasses. This molasses, containing 50%-plus sugar, yields 290-320 litres per tonne.

A third route is not to produce any sugar and ferment the entire 13.5-14% TFS into ethanol. From crushing one tonne of cane, 80-81 litres of ethanol can thus be obtained, as against 20-21 litres and 10-11 litres through the B-heavy and C-heavy routes respectively.

[the_ad id=”73763″]

FEEDSTOCKS DIVERSIFICATION

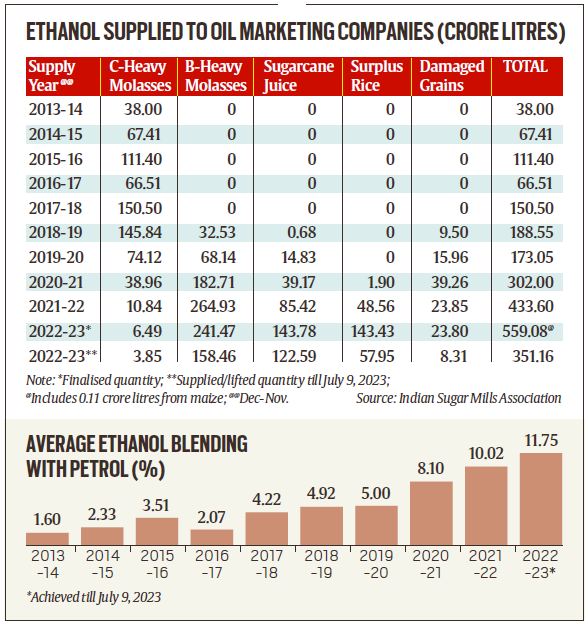

The table shows ethanol supplies by mills/distilleries to OMCs soaring from a mere 38 crore litres in 2013-14 to an estimated 559 crore in 2022-23. Moreover, there has been a significant diversification of feedstocks from C-heavy to not only B-heavy molasses and direct sugarcane juice, but even rice and other foodgrains.

Ethanol yields from grains are actually higher than from molasses. One tonne of rice can produce 450-480 litres of ethanol, while it is 450-460 litres from broken/damaged grains, 380-400 litres from maize, 385-400 litres from jowar (sorghum) and 365-380 litres from bajra and other millets. The yields are linked to starch content: 68-72% in rice, 58-62% in maize and jowar, and 56-58% in other millets.

However, though more ethanol can be produced from grains than molasses, the process is longer. The starch in the grain has to first be converted into sucrose and simpler sugars (glucose and fructose), before their fermentation into ethanol by using yeast (saccharomyces cerevisiae). Molasses already contains sucrose, glucose and fructose.

YEAR-ROUND PRODUCTION

Some leading sugar companies — including Triveni Engineering & Industries Ltd, DCM Shriram and Dhampur Sugar Mills — have installed distilleries with the flexibility to operate on multiple feedstocks and, hence, round the year.

The multi-feed distillery, commissioned in April 2022, has three 2,800-tonnes silos for storing grain, besides facilities for milling into flour, liquefaction (converting starch into glucose and fructose), fermentation (to 15% alcohol), distillation (to 94% spirit) and dehydration (to 99.9% ethanol).

“India’s ethanol programme is no longer reliant on a single feedstock or crop. Earlier, it was molasses and cane. Today, it’s also rice, maize and other grains. Diversification of feedstocks will minimise supply fluctuations and price volatility on account of any one crop,” said Tarun Sawhney, vice chairman of Triveni Engineering, which has increased its total distillery capacity from 320 KLPD to 660 KLPD since 2021-22 and plans to further expand to 1,110 KLPD by 2024-25.

THE BOOST

The flexibility and incentive for mills/distilleries to use multiple feedstocks has largely come from the Modi government’s policy of differential pricing. Till 2017-18, the OMCs were paying a uniform price for ethanol produced from any feedstocks.

From 2018-19, the Modi government began fixing higher prices for ethanol produced from B-heavy molasses and whole sugarcane juice/syrup. The idea was to compensate mills for revenues foregone from reduced/nil production of sugar.

The stimulus that this has given to ethanol production can be seen from its all-India average blending with petrol touching 11.75% in 2022-23, as against 1.6% in 2013-14 (chart).

The incorporation of new feedstocks for ethanol production can create new demand for grains. Uttar Pradesh is a major sugarcane grower, just as Bihar is in maize. If their farmers were to supply rice, barley and millets as well to distilleries, these two states could well “fuel India” the way Punjab, Haryana or Madhya Pradesh “feed India”.

The current year might be an exception, with likely pressure on domestic availability/stocks of cereals and sugar from El Niño-induced monsoon uncertainties. While the Modi government has already banned exports of wheat, sugar and non-parboiled non-basmati rice, it hasn’t put any brakes so far on the ethanol blending programme.

BYPRODUCT BENEFITS

Distilleries are often synonymous with pollution. The liquid effluent (spent wash) generated during alcohol production can pose serious environmental problems, if discharged without proper treatment.

But the new molasses-brd distilleries have MEE (multi effect evaporator) units, where the spent wash is concentrated to about 60% solids. The concentrated wash is used as a boiler fuel along with bagasse (the fibre remaining after crushing sugarcane) in 70:30 ratio. The resultant ash coming out from the incineration boiler in dry form contains up to 28% potash, which can be used as fertiliser.

The spent wash from grain distilleries similarly goes into a decanter centrifuge, which separates the liquid from the solid. This is followed by concentrating the liquid in MEE units and drying it along with the wet cake from the decanter. The resultant by-product, DDGS or distillers’ dried grain with solubles, is sold as animal feed.